If you tread lightly on the planet in life, why wouldn’t you want to leave this world the same way? Francesca Price investigate the growing number of green alternatives when it comes to natural funerals

If you lead a considerate life, trying to do the right thing by others and treading lightly on the planet, then why wouldn’t you die the same way you’ve lived? There are a growing number of green alternatives when it comes to how you leave this world, writes Francesca Price

When Steve Hill woke up in the early hours of the morning, his wife Helen was dead. He had been expecting something to happen that night. After four-and-a-half years fighting breast cancer, Helen’s strength had gone. She had pulled her oxygen tube out earlier in the evening, just before Steve got into bed beside her, and she’d asked him not to put it in again.

Their two young sons were asleep in the large Balmoral house. Steve woke Kane (six) and Nico (four) and brought them in to see their mum. They went straight to her, held her and cried. Over the next three days, as family and friends came and went, Helen remained in her bed. Her sisters chose her clothes and helped put ice packs around her body to prevent it deteriorating. A friend from the cosmetics company MAC, which Helen had launched in New Zealand, did her makeup; another friend styled her hair.

Steve slept next to her every night. Kane and Nico came in whenever they wanted to have a cuddle and talk to Mum. When the wicker coffin that Helen had chosen arrived, they placed it in the bedroom and the boys jumped up and down inside it. Helen was rarely alone. The house was full of people and activity. One of Helen’s sisters helped Steve carve messages into the flax that would be placed on top of her casket. Someone else arranged for a flock of doves to be released at the funeral.

Steve believes these three days helped them all come to terms with Helen’s death. “Having Helen in the house made us accept the reality that she was dead. We had the space to be with her, talk to her and say what we wanted.” He and Helen had discussed the funeral before she died; they wanted it to be as natural as possible. They didn’t want her body smelling of “nasty embalming chemicals” or to be whisked away to a morgue, out of sight.

The morning after Helen died, Steve rang a funeral director specialising in natural funerals. There are several now operating in New Zealand, mostly run by one or two people who are determined to offer not only a personal service, but also an eco-friendly one. Embalming is kept to a minimum, the coffins on offer range from simple cardboard to designer strips of ply sewn together with jute. Mattresses are made of wool and cotton, and family involvement is encouraged every step of the way. Not only does this make the funeral more personal, it keeps costs down as well.

Steve and Helen chose a company called State of Grace, a two-woman team operating out of west Auckland. Deb Cairns and Fran Reilly arrived the next day to place ice packs around Helen’s body and talk to her family about what they wanted. State of Grace had been operating for only a year, and the women were still feeling their way into a business traditionally dominated by grim men in black suits. They had been given well-meaning advice—“don’t have any physical contact with your clients”, “don’t show your emotions”—but from the beginning, Deb and Fran found this impossible. “If somebody’s crying, the first thing you want to do is hug them,” says Deb.

Over the three days Helen was at home, they were constantly at her and Steve’s house, changing the ice packs with help from the boys and assisting with funeral arrangements. “Helen was a very beautiful woman, and she seemed to grow more beautiful in the time we were there,” says Deb. “I remember the day we dressed her, she almost seemed to be helping us. It was so easy putting her clothes on, we thanked her as we went along.” The whole experience was a very positive, very loving one. “It was everything that Helen and Steve had hoped for,” says Deb.

The idea of a funeral as positive sits uncomfortably with the many of us who have little or no direct experience of death. With no festivals and few rituals around death or dying, many New Zealand families tend to see death as a subject to discuss if and when they are forced to confront it. Funerals aren’t generally regarded as community events, but private affairs where bodies are taken away quickly to a morgue, and buried or cremated inside a closed-lid casket.

Being part-Maori, Steve was fortunate to have witnessed another way of grieving. At a tangi, the body of the deceased is kept on the marae and watched over by relatives for the days before its burial. To Steve, keeping Helen at home seemed entirely natural.

Not your usual suits; Deb Cairns (left) and Fran Reilly from State of Grace

The birth of natural funerals

When State of Grace started, Deb and Fran wanted to help families keep their loved ones at home. Deb had very little contact with death until a friend was diagnosed with breast cancer in her early forties. They had been playcentre mums together, and had seen each other’s kids grow up. When her friend realised she was going to die, she asked Deb and some other friends to help her die at home. “She’d had all her babies at home, and saw no reason why she should go elsewhere to die,” says Deb. It was a profound experience for all involved and, surprisingly for Deb, the beginning of a new career. “It felt so right to be caring for her ourselves, not to be handing it over to someone else. I wanted to help other people do it,” she says.

Deb started researching natural funerals. Although a relatively new concept in New Zealand, there were natural funeral directors in the US and Europe. Deb contacted Californian woman Jerrigrace Lyons, who is credited with starting the home funeral revolution in the US. She agreed to come to New Zealand to hold a workshop. At the end of it, Deb and her friend Fran set up State of Grace.

Although both women had run successful businesses before, this was a radical departure. “We used to scream every time the phone went,” says Deb, but they were helped by the generous support of other funeral directors. Their frequent nightmares “of the bottom falling out of a casket, or getting the wrong person” have, thankfully, never been realised.

At work in their warehouse space in New Lynn, both women now seem completely at ease with their new line of work. Deb is drilling handles onto a beautiful white coffin for a funeral that afternoon, while Fran is dressing an older man who has died a few days before. I am introduced to him, and find myself saying hello. As I sit and watch them work, I am surprised how quickly it feels normal to be around a dead body. The mobile goes constantly, either with requests from the families they are working for or with calls from one of their kids—the two women have seven children between them—and they dart between last-minute funeral details and promises to be at an after-school hockey game.

It’s a homely scene. When she’s not drilling in handles, Deb runs up straps on her sewing machine to carry the David Trubridge-designed casket. Fran oils a lovely wooden coffin before heading off to have the hearse mudflap fixed. Like any partnership, there are little trade-offs. “I can’t do earrings,” says Deb, “and Fran can’t do false teeth.”

For the funeral today, they are dressed in sombre colours—deep greens, navy blues—but both women look stylish and there’s not a black tailcoat in sight. “We come at this as women and mothers,” says Fran. “We meet people when they are at their most vulnerable and you get to know them pretty quickly. It would be impossible not to feel compassion or to shed a few tears—especially when there are children involved.”

It was their credentials as mothers, rather than funeral directors, that made Steve Jamieson ring State of Grace when his 17-year-old son, Juke, died in April after a ten-month battle with cancer. Juke Jamieson was a prefect at Westlake Boys High School on Auckland’s North Shore when doctors discovered a tumour the size of a rugby ball in his stomach. Despite intensive chemotherapy and countless operations, Juke didn’t get better. At the end of his time in Starship Children’s Hospital he had accrued 1,813 beads of courage—one for every major procedure he’d been through. Two weeks before his death, Juke asked to come home to be with his family and friends. The friends set up camp in his room and didn’t leave until his body was taken away.

Steve heard about State of Grace while Juke was at Starship. “They told me it was run by these two women who didn’t like doing children’s funerals, because it’s too upsetting. I thought, That’s exactly the type of care I want. I want my son to have a mother’s touch.”

It’s a homely scene. When she’s not drilling in handles, Deb runs up straps on her sewing machine. Fran oils a lovely wooden coffin before heading off to have the hearse mudflap fixed. Like any partnership, there are little trade-offs. “I can’t do earrings,” says Deb,

“and Fran can’t do false teeth”

Steve remembers that when Deb walked in, she went straight over to Juke and said, “He’s beautiful”. Deb helped to facilitate the type of funeral they wanted for their popular son: full of tributes from friends and music he loved. On the day, 2,000 people attended the service, and as Juke’s body was carried out to his favourite Killers song, students from his school rose and performed a haka.

Good grief

While most funeral directors would accommodate a family’s personal requests, a spouse or parent in grief doesn’t always know what they’re looking for. Natural funeral directors will suggest ways of making the funeral unique and offer a high level of support for all those involved. They also have a range of services you might not find elsewhere, such as sustainable caskets and the option of keeping the body at home before burial. They try to steer clear of chemicals, embalming only 15 percent of the bodies they work with, compared with 85 percent at other funeral parlours. But in some cases embalming can be a godsend. “If people have had invasive surgery or cancer, it’s often the best option. And sometimes families are just too exhausted to keep on caring for the body,” Deb explains.

A natural funeral is an empowering event for all involved and can play an important role in the grieving process. Rather than dealing with their emotions privately, family and friends are brought together to make arrangements and have the opportunity to share their feelings. When Deborah Jones lost her husband Richard earlier this year, she knew how important it was to express her grief. She’d worked as a counsellor and therapist, and had been through another serious loss when her second child, Caleb, died of a drug overdose at 19. “The body remembers grief,” she says. “If it’s not shared, the body stores it up and it comes out in other ways. We have to talk about death, otherwise all we have is the fear of death.”

Many natural funeral directors offer a service known as a ‘living will’, which enables someone to state exactly how they want to be cared for, before and after their death. Far from being morbid, it gives rights to the dying at a time when they may not be able to express their wishes.

Deborah and Richard had talked about his death. When the time came, Deborah says it was like a birth where she acted as the midwife. “He took five big breaths and didn’t let the last one out.” Deborah knew what Richard wanted. His coffin was carried down to rest on the beach, beside their home, before being taken away for cremation. His ashes will be scattered over the bay, just like their son’s.

Remarkably, after losing two loved ones Deborah doesn’t fear death. “It’s an awesome thing,” she says. “When someone dies, the world stops. It’s like a veil is pulled aside for a while, and life becomes about loving and honouring one another.”

Three feet under

At a natural burial park, the body isn’t embalmed but placed in a biodegradable coffin and buried just one metre—rather than the traditional six feet—below the earth’s surface. At this depth, bodies decompose quickly and benefit the surrounding soil. A tree is planted on top of the coffin, which grows to become a part of a forest or bush. There is no headstone, but loved ones can navigate their way around the site with the help of a map or GPS coordinates. This way, a burial has a positive impact on the environment, creating a new, living ecosystem rather than depleting trees and polluting the soil.

In the UK, where there are over 300 sites, natural burials account for six to seven percent of all burials. The first New Zealand natural burial site opened in Makara, Wellington, in March 2008. Six of the plots have been filled and there is a waiting list of 100. There has been provision for natural burials at Waikumete Cemetery in Waitakere for a number of years.

There are plans to open six more natural burial parks in Kapiti, Waitakere, Wanganui, Christchurch and Nelson.

Eco-caskets

- Handle with Care: Made in Nelson from sustainably grown timber, jute webbing and water-based glue, Handle with Care caskets are delivered flat, and come with a biodegradable cornstarch liner. Their simple design and wooden dowels ensure they’re easy to put together, and their natural finish can be personalised with art or messages. “We aim to provide a dignified, affordable product while considering the environment at every stage of production,” says Mike, who suggests clients buy in advance to reduce the stress for others.

www.handlewithcare.net.nz - Return to Sender: Styled for the aesthetically minded, these award-winning timber coffins come in three models, each with a wool-fleece mattress and pillow. The curvaceous Artisan has low sides, ideal for open caskets and mourners wanting to sit beside the deceased rather than having to stand and peer down into a box. Essence is a statement in minimal elegance and is extra light, making it easier for older children to help carry. The classic Archetype is made with sustainably harvested rimu.

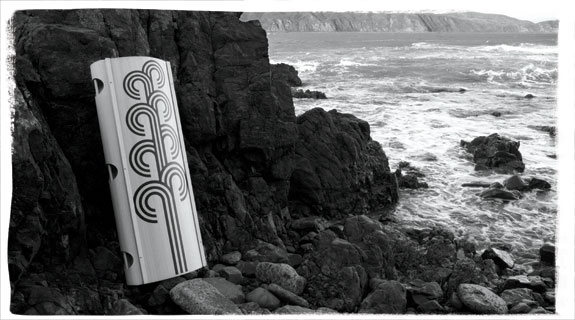

www.returntosender.co.nz - David Trubridge Design: If you’ve spent any time on eco-designer David Trubridge’s elegant, boat-like chaise lounges, you’ll no doubt want to launch your journey into the next life in his equally eye-catching eco-casket. Made from natural plywood and lashed together with jute fibre, the Trubridge coffin is a model fitting a designer of international repute, as well as the style-conscious deceased.

www.davidtrubridge.com - Tender Rest: The Bambino is a beautiful cradle-inspired bamboo casket designed specifically for infants. It has natural rope handles and a wood inner. Adult caskets come in smooth bamboo or economical pine plywood and are finished with organic, citrus-scented wood-oil. The award-wining Nextgen model has a gentle flowing shape, curved base, low sides and a 100 percent cotton quilted mattress. For those keen enough to buy in advance, there’s an optional bookshelf/wine rack conversion kit for ‘pre-use’.

www.tenderrest.co.nz